The Recession Watchguard: Predicting the 2025–2026 Recession with Data, Trends, and Hidden Signals

A Data-Driven Forecast on the Imminence of Recession, Credit Crises, and Policy Risks in 2025-2026

The Calm Before the Storm. Are We on the Edge of a Recession?

Every financial crisis starts the same way; first as a whisper, then a debate, and finally, an undeniable reality. Right now, we’re in that crucial in-between phase. Markets are jittery, warnings are flashing, and yet, the full picture remains just out of focus. But the question remains: Have we already crossed the point of no return?

This research isn’t about fear-mongering or making bold predictions for the sake of it, but it’s about looking at the hard data; yield curves, credit spreads, labor market shifts, liquidity pressures, and understanding what they’re really telling us. Beyond the headlines, and propaganda, patterns signaling a major economic shift are forming.

Recessions don’t happen overnight, but the signs always appear before the downturn truly begins. Whether you’re an investor, a business owner, or just someone who wants to stay ahead of what’s coming, I hope this deep dive will help you connect the dots. The goal isn’t to panic it’s to be prepared. Because in times like these, knowing what’s next makes all the difference.

1. Key Economic Indicators of Recession Risk

Yield Curve Inversion and Term Premium: A classic warning sign of recession, the yield curve (spread between long-term and short-term Treasury yields) has been inverted for an extended period. In mid-2023 the 2-year/10-year Treasury spread reached deeply negative levels (around –100 basis points), a pattern that historically precedes recessions by 6–18 months (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute).

Recently, long-term yields have surged as investors demand a higher term premium for holding long bonds amid fiscal and inflation uncertainties. The New York Fed’s estimate of the 10-year term premium jumped above +0.50% (50 bps) for the first time since 2014 (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters). This resurgence of term premium has led to some “dis-inversion” at the long end – for example, the 2-year to 30-year yield gap reached +64 bps in early 2025, the steepest since the Fed’s hiking cycle began (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters). An inverted curve still signals caution, but the recent steepening (a so-called “bear steepener” driven by rising long rates) suggests markets are pricing in persistent inflation or deficits rather than an imminent Fed rate cut. Notably, the New York Fed’s recession probability model based on the yield curve had spiked to very high levels in 2023 (well above 50% odds of a 12-month-ahead recession) when the curve was most inverted. The yield curve is still showing warning signs as of early 2025, but the unusual term premium dynamics and Federal Reserve interventions may have obscured its signal (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters).

Treasury Bond Spreads and Liquidity: Beyond the 2–10 year spread, other Treasury market indicators underscore stress. The spread between 3-month T-bills and 10-year bonds was also deeply negative in 2023 – an inversion often viewed as even more predictive of recession.

However, by late 2024 and early 2025, rising long-term yields pushed 10-year rates to ~4.0–4.5% while some short rates eased, shrinking the inversion. This volatile rate environment reflects an uneasy equilibrium: Investors are weighing a possible economic slowdown (which would normally lower long yields) against persistent inflation and heavy Treasury supply (which push yields up). The result has been higher long-term yields with greater term premiums, a potentially dangerous mix for debt sustainability (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters). Importantly, U.S. Treasury market liquidity has been a concern – at times in 2022–2023, poor liquidity in off-the-run Treasuries raised fears of a “Treasury market seize-up.” The Treasury Department and Federal Reserve have taken steps to bolster liquidity, such as planning regular buybacks of older bonds starting in 2024 to prevent dysfunction (Debt buyback program set to improve liquidity, says US Treasury ...). These actions aim to ensure the crucial Treasury market doesn’t become the source of a crisis itself. So far, yields’ rise has been orderly, but stress bears watching in this backbone market.

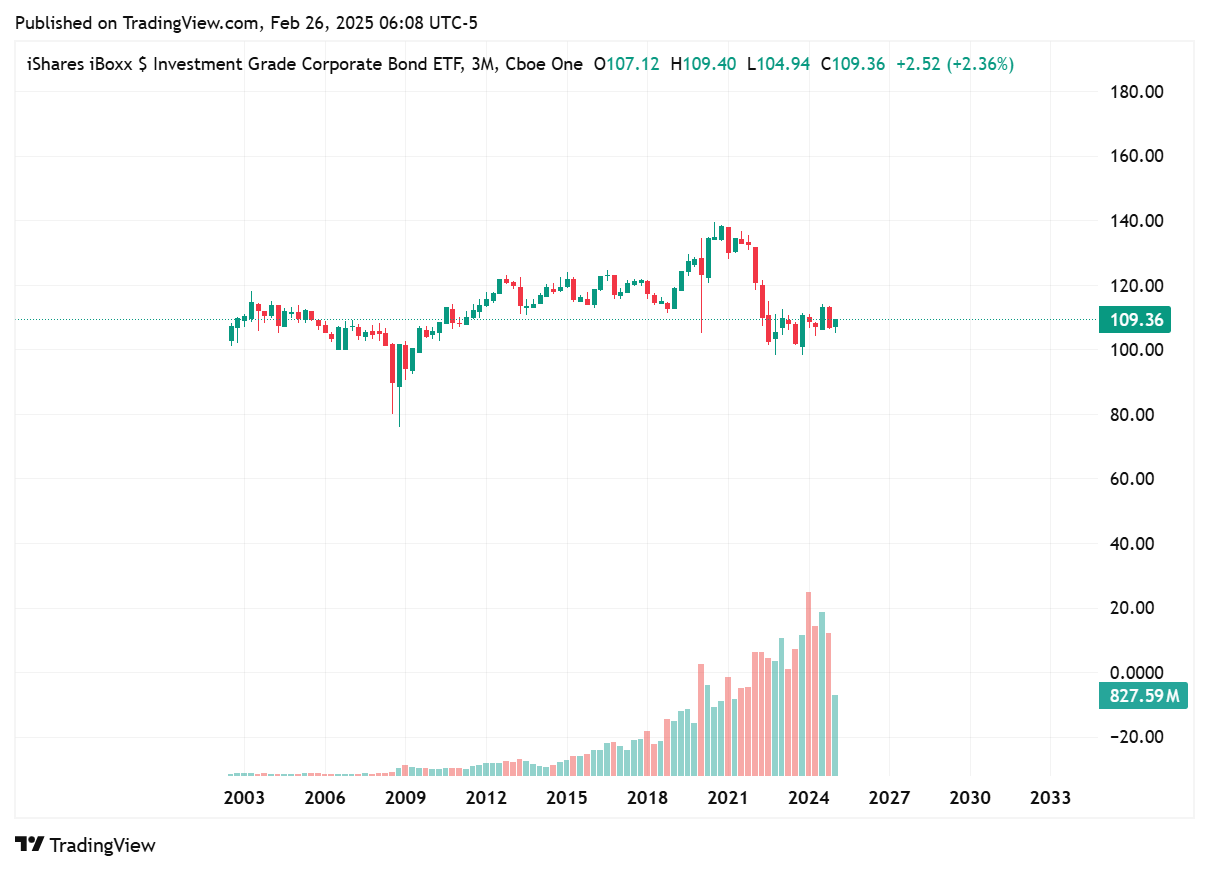

Credit Spreads and Corporate Bond Market Stress: In contrast to the warning from Treasuries, credit markets until recently have shown remarkable calm. Corporate bond credit spreads – the extra yield above Treasuries that investors demand to hold corporate debt – remain historically tight. The average option-adjusted spread on investment-grade U.S. corporate bonds fell below 0.80% in late 2024, its lowest level since 1998 (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab). Likewise, high-yield (“junk”) bond spreads tightened to about 2.5% (250 bps) in November 2024, the lowest since 2007 (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab). Such tight spreads indicate investors are not demanding much risk-premium, reflecting optimism about corporate health and low default risk. Typically, spreads widen when recession fears rise (as investors worry about defaults). The current tight spreads suggest little market-implied stress – a stark divergence from the inverted yield curve’s signal. However, this could imply complacency. There are early signs of strain beneath the surface: U.S. corporate bankruptcy filings surged in 2024 to the highest level in 14 years (694 filings, the most since 2010) (Analyzing the Rise in Corporate Bankruptcies - LPL Financial). Many firms, especially highly leveraged ones, are feeling the pinch of higher interest rates after years of debt buildup. Credit Default Swap (CDS) indices for corporate debt have remained relatively stable so far, but any sudden default by a major borrower could rapidly widen CDS spreads. In short, corporate credit markets have not (yet) priced in recession-level distress, but default rates are creeping up from cyclical lows. If economic conditions deteriorate, a snap repricing – widening of spreads and CDS – could occur, tightening financial conditions abruptly.

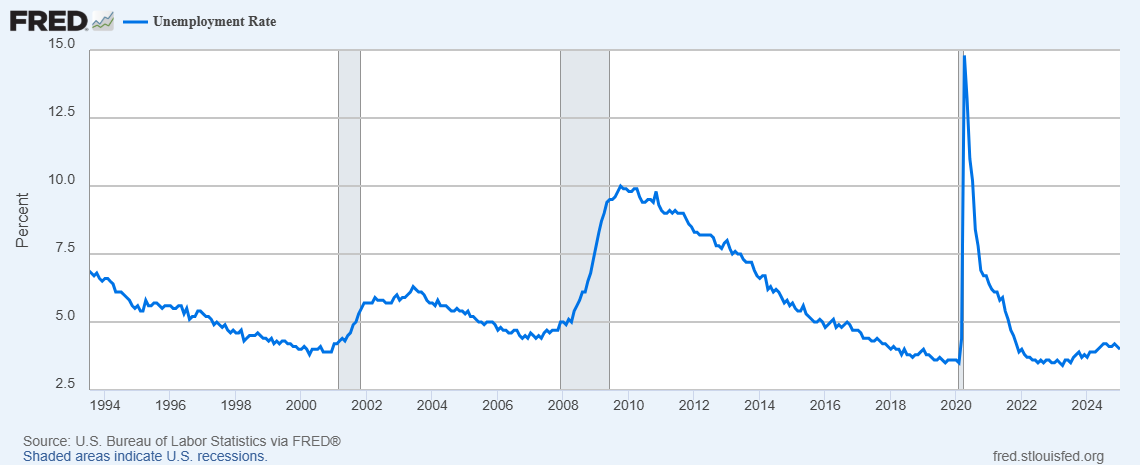

Labor Market Trends: The job market has been a bulwark against recession, but there are emerging cracks. Headline unemployment in the U.S. remains low (around 3.8% as of early 2025), but it has risen off the trough of 3.4% seen in April 2023 (The Sahm Rule Trigger: Is the United States in a Recession?).

This gradual rise in the jobless rate – now about +0.9 percentage points above its low – actually triggered the Sahm Rule in mid-2024, a rule of thumb where a 0.5 point uptick in the 3-month average unemployment rate signals a recession may be underway (The Sahm Rule Trigger: Is the United States in a Recession?). While not definitive, it shows the labor market’s expansion has cooled. Other indicators confirm some deterioration: Temporary help employment, often a leading indicator, has been declining.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that declines in temp agency jobs tend to precede broader employment downturns by 6–12 months (What happened to temps? Changes since the Great Recession : Monthly Labor Review: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). Indeed, U.S. “temp” jobs peaked in late 2022 and by July 2023 were down ~4.7% year-over-year – a drop comparable to pre-recession periods (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute) (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute). Employers often cut temporary and contract staff first when they sense trouble, so the ongoing slide in temp hiring is a warning flag. Additionally, labor force participation remains slightly below pre-pandemic levels (62.7% in Q3 2024 vs ~63.4% in Feb 2020), meaning about 1.7 million “missing” workers compared to pre-COVID trends (Understanding America's Labor Shortage). A constrained labor force can both prop up wage growth (fewer workers available) and limit growth potential. Wage growth itself has shown signs of stagnation in real terms: Nominal wages cooled from ~5% annual gains in 2022 to around 4% in 2023, roughly on pace with inflation. Real average hourly earnings only rose about 1.1% in the year through Feb 2024 (Real average hourly earnings increased 1.1 percent for year ending February 2024 : The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics), after falling behind inflation in 2022. Slower wage growth alongside rising prices had crimped consumers’ purchasing power, although as inflation eased some real wage gains returned. Bottom line: The labor market is no longer tightening; it’s loosening at the margins – higher unemployment, fewer job openings, falling temp jobs, and moderating pay increases all hint at an economy cooling off. Historically, once unemployment begins to trend up from a trough, a recession often follows within a year or so, barring an abrupt reversal.

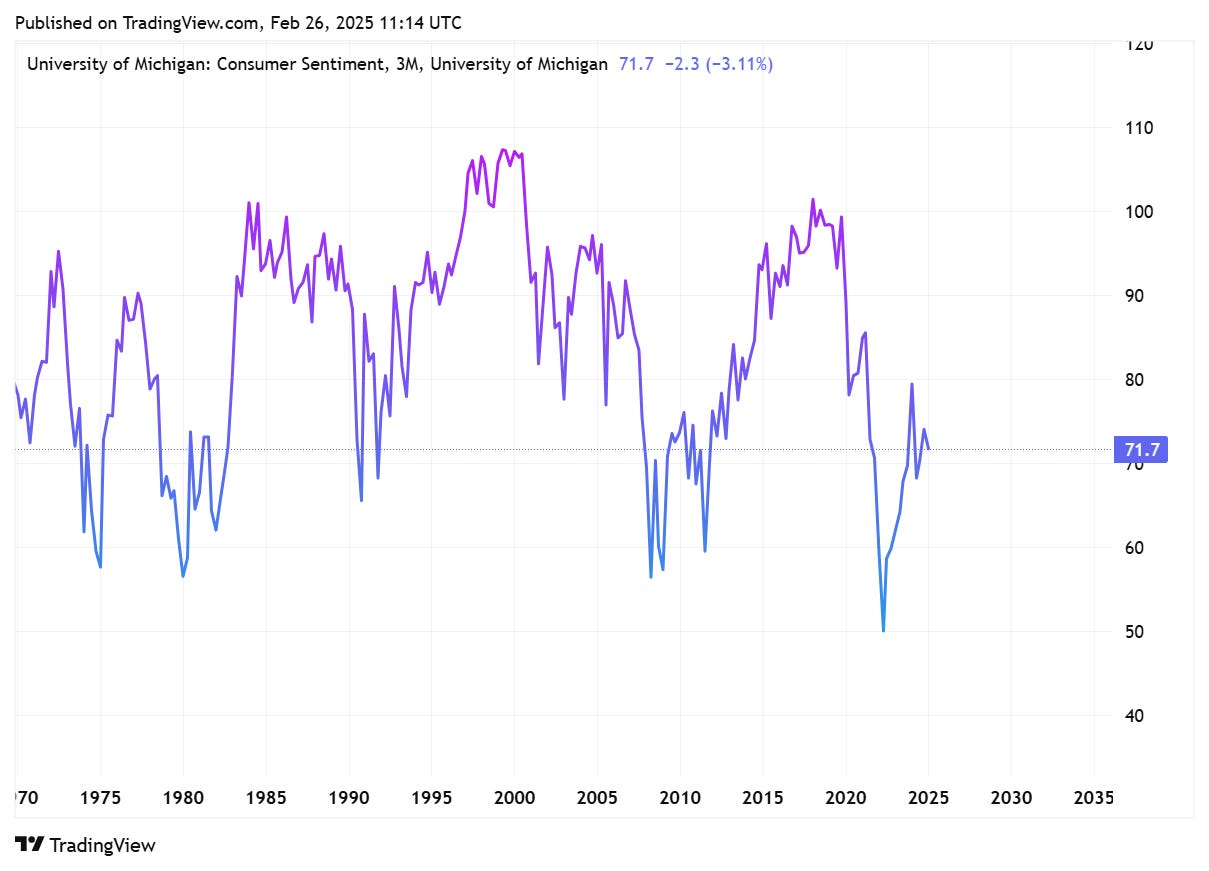

Consumer Sentiment and Spending Patterns: Consumers have sent mixed signals. Consumer sentiment plunged to record lows in mid-2022 (the University of Michigan Sentiment Index hit ~50, reflecting high inflation angst) and has recovered since then, but sentiment remains relatively subdued. By late 2024, the index had risen into the 70s – for instance, 74.0 in December 2024, up from 69.7 a year prior (Consumer outlook on the rise, despite worries with policy shifts ...). This recovery suggested improved feelings due to cooling inflation and a strong job market. However, sentiment dipped again in early 2025 as inflation worries ticked up – the index fell back to 64.7 in Feb 2025 (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News).

Consumers’ expectations for the economy’s near-term fell significantly in that survey, and notably, buying conditions for big-ticket durable goods dropped 19% as people feared new tariffs would drive prices higher (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News) (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News). This highlights how policy uncertainties (like trade tensions) can quickly sour consumers’ mood. On the spending side, households have been shifting their habits: after a stimulus-fueled boom in goods during the pandemic, demand has rotated back toward services. In 2023, overall retail and food services sales rose a modest 3.2% from the prior year – a growth rate flattered by inflation.

The strongest gains were in food services (restaurants sales +11% in 2023) while many goods categories were flat or falling in real terms (Consumer Spending Ends 2023 on a High Note While Industrial ...). Shoppers became more value-conscious, hunting for discounts especially as pandemic savings dwindled. Big-box retailers noted consumers pulling back on discretionary purchases like electronics and furniture, even as travel and dining out remained robust. This divergence suggests that while consumer spending overall has held up (preventing recession so far), it’s been propped up by service sector strength and continued employment gains. Any weakening in the job market could swiftly translate to reduced consumption. Indeed, the drop in consumer confidence in early 2025 is a warning that household spending might downshift ahead. With higher interest rates biting (making credit card balances and auto loans costlier) and excess savings largely spent, the consumer is more vulnerable going forward. Retailers have already felt some stress – inventory gluts in 2023 forced heavy discounting, and some chains serving low-income cohorts reported sales declines as those consumers retrenched. The key question is whether resilient consumer spending (roughly 70% of the economy) will continue to offset weakness in other areas; the latest sentiment trends suggest mounting caution.

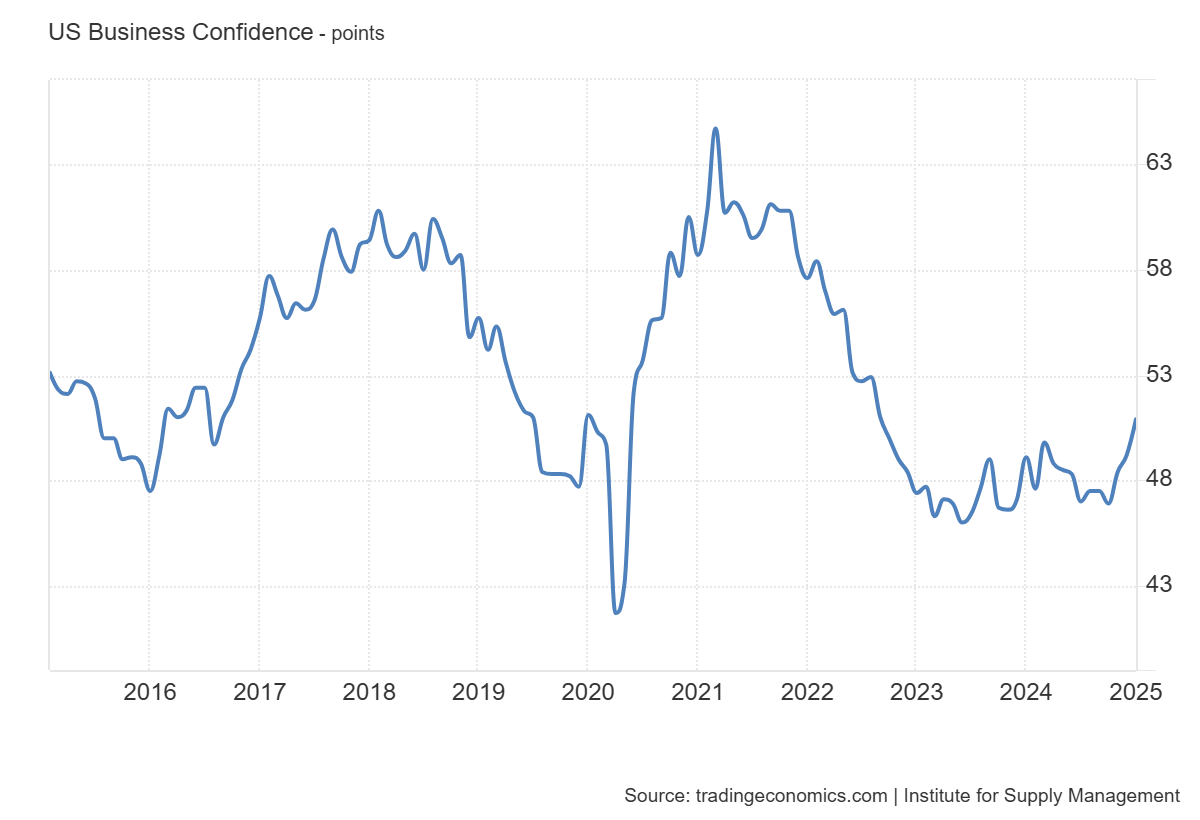

Manufacturing PMI and Corporate Earnings Divergences: The industrial sector has been in a funk even as corporate America’s overall profits stayed high.

Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) surveys spent much of 2023 below the breakeven 50 level in the U.S. and even lower in Europe and China, indicating contracting factory activity. By late 2024, a stark divergence had emerged: manufacturing output was falling at the sharpest rate since the 2008–09 crisis (excluding the initial COVID shock), while the service sector was booming with growth at multi-year highs (Flash PMI data shows US economic outperformance widening in December | S&P Global ). S&P Global noted this is the widest gap on record between a shrinking manufacturing sector and an expanding services sector among major economies (Flash PMI data shows US economic outperformance widening in December | S&P Global ). Such a split is unusual – typically manufacturing downturns presage broader recession, but so far the service economy’s strength (fueled by consumers) has kept aggregate growth positive. This asynchronous cycle is also seen in corporate earnings. Many goods-producing and cyclical companies (industrials, materials, some retailers) have seen earnings growth stall or margins compress due to higher input costs and weak demand. In contrast, mega-cap technology and services firms have largely exceeded earnings expectations, buoyed by secular demand (e.g. digital services) and better pricing power. As a result, corporate earnings divergences are significant: a few sectors (tech, communications, energy earlier in 2022) drove outsized profit gains, while others lagged. Market commentators like those at Bridgewater Associates warned in 2022–2023 that overall U.S. corporate profits were at unsustainably high levels relative to GDP and would likely revert downward (Ray Dalio's Hedge Fund Sees More Pain For Wall Street - SPDR S&P 500 (ARCA:SPY) - Benzinga). Indeed, by 2024, S&P 500 companies saw only modest earnings growth and even declines in certain quarters (excluding the top tech firms). Small businesses and startups, which don’t have as much cushion, struggled with higher labor and borrowing costs – reflected in sentiment surveys like NFIB small business optimism which remained historically low. In summary, manufacturing and trade-related sectors are already in a form of recession, even as services and large corporate earnings averages mask that weakness. This divergence can’t persist indefinitely – either consumer/services cool off, dragging the whole economy down, or manufacturing finds a bottom if the broader economy keeps growing. Policymakers are watching these mixed signals closely: a sustained PMI contraction usually foretells cutbacks in capital spending and employment in manufacturing, which can spill over if demand for services also slows. The corporate earnings picture suggests that while aggregate profits have held up, the underpinning is narrow – if the “last engines” of growth (like consumer tech spending) sputter, overall earnings could fall and lead firms to cut payrolls or investment, reinforcing a downturn. That risk is rising as interest rates stay high.

2. Expert Forecasts and Institutional Reports

Federal Reserve Communications: The Federal Reserve’s official stance as of late 2024 was cautiously optimistic – a soft landing (bringing down inflation without a recession) was seen as the baseline. Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues have noted the resiliency of growth and jobs even under rapid rate hikes. In fact, the Fed’s staff economists famously backtracked on their recession call: in mid-2023, the Fed staff had projected a “mild recession” would hit by year-end, but by the July 2023 meeting they reversed that prediction given the economy’s surprising momentum (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute). Fed officials emphasize that they are not forecasting a recession, though they acknowledge downside risks. Recent Fed minutes and speeches highlight vigilance for any “credit crunch” or fallout from past tightening. For example, Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr recounted how the Fed acted swiftly in March 2023 to contain banking sector stress (Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse) and that those crisis-management tools remain ready if needed (Speech by Vice Chair for Supervision Barr on financial stability - Federal Reserve Board). The Fed has also published research on leading indicators: the New York Fed’s yield curve model (which at one point showed ~60% recession probability) and the San Francisco Fed’s work on tightening lending standards both inform their risk view. While the Fed doesn’t publicly put odds on a recession, communications suggest they see a narrow path to cooling inflation with only a modest rise in unemployment – essentially a soft landing. However, they continually mention uncertainties: lagged effects of monetary policy, global risks, and not wanting to repeat 1970s stop-go errors. In sum, Fed communications acknowledge the inversion of the yield curve and other red flags but maintain that a downturn is not inevitable. They have signaled policy flexibility – pausing rate hikes as necessary and even cutting if the economy weakens sharply – but also a commitment to keep inflation heading down. The Fed’s dual mandate means it will try to avoid a collapse scenario, yet history shows the Fed often only recognizes recessions once they are well underway. Internally, the Fed will be watching data like a hawk; any rapid rise in joblessness or financial turmoil would likely provoke a swift response (rate cuts, liquidity programs) to mitigate a collapse. In the meantime, their official forecast in the September 2024 Summary of Economic Projections still showed GDP growth around 1–2% for 2024 and 2025 and unemployment edging up to ~4.5% – hardly a recession, but a noticeable cooling from 2023’s pace.

Global Institutions – IMF and World Bank: International organizations have also tempered their outlooks while warning of risks. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its World Economic Outlook (Oct 2024) projected global growth around 3.0% in 2024, roughly the same tepid pace as 2023, and 3.3% in 2025 (As Inflation Recedes, Global Economy Needs Policy Triple Pivot). The IMF noted that a worldwide recession was avoided in 2023 thanks to strong U.S. growth and rebounding service sectors, but it cautioned that divergent outcomes exist beneath the surface – for example, Europe narrowly skirted recession and China’s recovery has been uneven. In commentary, the IMF has highlighted downside risks like sticky core inflation forcing more tightening, China’s property downturn spilling over, or debt distress in emerging markets. Similarly, the World Bank in January 2024 said the global economy is set for its weakest five-year period in three decades (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). They point out that global trade growth in 2024 is expected to be only half its pre-pandemic average, and financial conditions are the tightest in decades for developing countries (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). On a positive note, the World Bank acknowledged the risk of a near-term worldwide recession has receded compared to a year ago – largely because the U.S. and other advanced economies proved more resilient than feared (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). However, they immediately warn that geopolitical tensions and higher borrowing costs pose “fresh near-term hazards” that could derail growth (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). The medium-term outlook has darkened for many developing economies: over 40% of low-income countries are seeing reversals in living standards, and many are stuck with heavy debt and limited market access (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years) (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). Both IMF and World Bank underscore that if another shock hits – be it an oil price spike or financial crisis – many countries have less policy space now (higher debt levels, depleted buffers) to respond. These institutions urge proactive measures: the IMF talks of a “soft landing” requiring careful calibration and the World Bank calls for structural reforms and fiscal prudence to bolster growth. Notably, the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report (Oct 2023) pointed out vulnerabilities in the financial system (like stretched real estate valuations and non-bank leverage) that could amplify any shock. In summary, expert international forecasts don’t predict a collapse or even a full-blown recession for the U.S. or world in their base case – rather they expect sub-par growth with inflation gradually easing. But they repeatedly flag that the balance of risks is tilted to the downside. Any number of catalysts (higher-for-longer interest rates, geopolitical conflict, policy error) could cause the global economy to undershoot those modest forecasts.

Major Investment Banks and Think Tanks: Private sector economists have offered a range of views – from relatively sanguine to alarmed. On the optimistic side, Goldman Sachs notably cut its estimated probability of a U.S. recession. By March 2024, Goldman’s chief economist Jan Hatzius stated the U.S. has an 85% chance of avoiding a recession in the next year (i.e. only ~15% odds of recession) (Recession Outlook: US Has 85% Chance of Soft-Landing, Goldman Sachs Says - Business Insider). He cited resilient growth, improving inflation, and robust household finances as reasons that a hard landing was unlikely. Even by August 2024, when some data softened, Goldman’s recession odds were only bumped up to 25% (J.P.Morgan raises odds of US recession by year end to 35% | Reuters) – still well below the consensus. Morgan Stanley’s researchers similarly have leaned towards a soft landing scenario, expecting only a modest rise in unemployment (to ~4.1%) through 2024 and gradual rate cuts to support a continued expansion (Is the US Heading Towards a Soft Landing). J.P. Morgan, however, grew a bit more cautious mid-2024 – they raised their year-end 2024 U.S. recession odds to 35% (from 25% prior) after a weaker jobs report and signs of cooling wage growth (J.P.Morgan raises odds of US recession by year end to 35% | Reuters) (J.P.Morgan raises odds of US recession by year end to 35% | Reuters). JPMorgan’s view was that monetary policy was quite restrictive and would eventually slow the economy more materially, although their base case was still for only a mild downturn if one occurred. Bank of America and Wells Fargo have at times been on the bearish end, earlier predicting recession would hit by late 2023 or 2024, though many have since pushed those timelines out given the strong data. Outside of banks, independent economic think tanks have been waving caution flags. The Conference Board had persistently forecast a recession using its Leading Economic Index (LEI) – that index fell for 23 straight months through Jan 2024, a streak just one month shy of the record decline during 2007–09 (Conference Board gives up on U.S. recession call | Reuters). However, by February 2024 the Conference Board finally abandoned its recession call as some LEI components turned positive; they noted the LEI’s decline had slowed and “the index currently does not signal recession ahead” even though it remains near historically low levels (Conference Board gives up on U.S. recession call | Reuters). This climb-down underscores how confounding the economic signals have been. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve regional research provides insight: for example, the San Francisco Fed in May 2024 wrote that bank lending standards had tightened to degrees only seen around the 2008 crisis and 2020 pandemic (Economic Effects of Tighter Lending by Banks - San Francisco Fed), implying a considerable growth drag ahead as credit availability shrinks. The OECD and BIS (Bank for International Settlements) have each warned about the interaction of high debt and high rates. The BIS Annual Economic Report 2024 highlighted that despite tighter policy, crises have been averted so far (“so far, so good…”), but it “anticipates an increase in loan defaults” and sees significant risks for banks related to commercial real estate and private credit markets (BIS Warns of High Debt Levels and Loan Defaults). Additionally, some hedge fund and asset managers are openly bracing for a downturn: veteran investor Stanley Druckenmiller said in late 2022 and again in 2023 that he believed a recession was likely in the next year, arguing that markets hadn’t fully priced how higher rates would harm growth (Ray Dalio's Hedge Fund Sees More Pain For Wall Street - SPDR S&P 500 (ARCA:SPY) - Benzinga) (Ray Dalio's Hedge Fund Sees More Pain For Wall Street - SPDR S&P 500 (ARCA:SPY) - Benzinga). Similarly, noted “perma-bear” Nouriel Roubini and others have talked about the risk of a stagflationary debt crisis, where high inflation and high debt levels collide. While such dire predictions are outliers, they garner attention. In sum, expert opinions range widely – some see a soft landing as the most probable outcome, while others think a recession (albeit likely mild) is just delayed, not dodged. Notably, the consensus among Wall Street forecasters as of early 2025 was that if a U.S. recession comes, it would be relatively mild (unemployment perhaps peaking ~5–6%) and not a full financial collapse. But almost all agree that recession risks for 2025 are non-trivial, even if the exact timing is uncertain.

Institutional Warnings and Research: A few other pieces are worth noting: The OECD in its latest outlook projected global growth to stay below trend and specifically warned that Europe remains vulnerable to energy shocks and that China’s recovery is critical for the world economy. The OECD also pointed to fiscal challenges – many governments face high debt and will struggle to provide stimulus if a recession hits. The Bank of England and ECB, while outside the U.S. scope, have been tightening policy into their own weakening economies, raising the chance of recessions in the UK/EU that could spill over via trade and financial markets. And among think tanks, the Peterson Institute and others have published analyses suggesting that the U.S. may need to tolerate a higher equilibrium interest rate (r*) going forward – meaning the era of ultra-cheap money is over. If that’s true, some business models and asset prices predicated on low rates could face a reckoning. Hedge fund managers like Ray Dalio have even speculated the U.S. is headed for a “big debt cycle” reset – Dalio noted that with U.S. debt so high and the Fed eventually likely to ease to help the economy, there’s a risk of surging inflation or currency issues down the line (Ray Dalio: U.S. is facing a big-cycle debt crisis | Fortune). These perspectives underscore that beyond the next year, there are structural concerns (debt, demographics, de-globalization) that could shape the risk of economic instability. In summary, mainstream institutions foresee sluggish growth with contained risks, whereas some independent voices highlight the potential for more severe outcomes. A prudent takeaway is to weigh both views: the central forecast is not collapse, but the risk tail (low-probability, high-impact events) is fatter than usual in this environment.

3. Alternative and Overlooked Indicators of Instability

In addition to traditional metrics, several alternative indicators and risk factors deserve attention when assessing collapse or recession risk:

Geopolitical Risks (Trade Tensions and War): Geopolitics can rapidly undermine economic stability. The U.S.–China relationship, in particular, remains a wildcard. Escalating trade tensions – such as new tariffs or export bans – could hit business confidence and supply chains. Notably, recent consumer surveys showed Americans bracing for higher prices due to tariff announcements (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News), and policymakers have floated aggressive trade measures (e.g. restricting tech exports, higher tariffs on imports) that could provoke retaliation. A trade war resurgence would be stagflationary – raising inflation and damping growth. Beyond trade, the risk of outright conflict weighs on the outlook. The war in Ukraine continues to disrupt energy and food markets; a further escalation or spillover (for example, a NATO-Russia confrontation) would be a severe global shock. There are also flashpoints in Asia (Taiwan Strait) and the Middle East (Iran’s nuclear ambitions, tensions around Israel) that, while not base-case scenarios, could trigger financial panic or oil supply disruptions. Global risk monitors note that we are in a period of heightened geopolitical fragmentation, which increases the chance of policy mistakes and shocks. For instance, an intelligence or cyber warfare event between major powers could suddenly erode business and consumer confidence. Supply chain disruptions remain a related concern – while supply bottlenecks from the pandemic have mostly eased, new disruptions could emerge from geopolitical events (e.g. critical minerals or semiconductor supply cutoffs in a U.S.–China spat). Overall, geopolitical risk is hard to quantify but ever-present: it can act as a catalyst that tips an economy already on the brink into recession or worse. Businesses have responded by increasing inventories and diversifying suppliers (a form of resilience), but that only partially mitigates the threat.

Energy Market Fluctuations and Inflation: Energy prices are a traditional recession wildcard. In 2022, oil spiked well above $100/barrel after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, driving inflation to 40-year highs. Although oil has since moderated (trading in the $70–90 range through 2023), the market remains volatile. OPEC+ producers have shown willingness to cut output to keep prices elevated, and any supply shock – whether due to war, geopolitical strife (e.g. closure of a key shipping strait), or natural disaster – could send oil and gas prices soaring again. A significant surge in energy costs would quickly reignite inflation and squeeze consumers, likely forcing central banks to tighten further or delay rate cuts. The risk here is twofold: first, higher energy costs act like a tax, reducing disposable income and consumer spending (often a precursor to recession). Second, if central banks respond aggressively to the renewed inflation, they might induce the very downturn they seek to avoid. We saw a mini-version of this in mid-2023 when gasoline prices rose – consumer sentiment dipped and headline inflation upticked, complicating the Fed’s task. Beyond oil, natural gas and electricity prices (especially in Europe) remain a concern; Europe managed the 2022/23 winter energy crisis with conservation and luck, but remains exposed in coming years. Additionally, climate-related events (extreme weather) can create energy and food price shocks that feed into inflation – for example, heatwaves straining power grids or droughts affecting crops. These supply-side shocks don’t always cause full recessions on their own, but they can exacerbate a downturn or limit policy responses. Monitoring commodity markets and geopolitical developments in energy-producing regions is thus crucial. Encouragingly, strategic petroleum reserve releases and shifting trade flows have added some buffer. But the energy-inflation nexus will hang over the economy: any sign of an inflation resurgence from oil/commodities (as consumers in early 2025 feared with possible tariffs) could undermine the hard-won gains in price stability and force a difficult policy trade-off.

Private Credit and Shadow Banking Stress: One less-discussed vulnerability is the shadow banking system – financial activity outside traditional banks, such as hedge funds, private equity, money market funds, and non-bank lenders. In the past decade, with low interest rates, there was explosive growth in private credit funds and direct lending to firms by non-banks. These entities often provide loans to riskier borrowers (leveraged companies, commercial real estate projects) and rely on short-term funding themselves. The Bank for International Settlements has warned that high leverage in some parts of the non-bank sector poses a stability risk (Gabriel Makhlouf: Publication of the Financial Stability Review 2024:2). Thus far, we haven’t seen a major blow-up, but stress is building: higher interest rates mean higher debt servicing costs for borrowers of private credit, which could lead to rising defaults. Unlike regulated banks, shadow banks don’t have the same capital cushions or access to the Fed’s discount window (in most cases), so a failure or liquidity crunch there can spiral quickly. For example, the UK’s liability-driven investment (LDI) funds crisis in 2022 (where pension funds using leverage faced margin calls) showed how obscure corners of the market can create systemic tremors, requiring the Bank of England to intervene. In the U.S., money market funds have grown and could face redemption pressures if market interest rates become more attractive than yields they offer – though the Fed’s reverse repo facility helps backstop that for now. Commercial real estate (CRE) is a focal point: Many loans for offices, hotels, malls, etc., are held in non-bank vehicles or as commercial mortgage-backed securities, not just on bank balance sheets. As remote work drives office vacancy high and refinancing gets tougher, defaults are climbing. Indeed, office loan default rates have surged – an estimated 11% of office property loans by big banks are delinquent or defaulted (Big Banks Face 11% Default Rate in Commercial Real Estate Test), and Fitch Ratings projects overall CMBS (commercial mortgage-backed security) delinquency to roughly double from ~2.3% in late 2023 to about 4.5% in 2024 (US Commercial Real Estate Deterioration to Increase in 2024, Led ...). Private credit funds that helped refinance a lot of real estate and corporate debt in recent years might encounter losses or investor withdrawals. Since these shadow banks aren’t as scrutinized, a “credit event” could happen there under the radar and then suddenly affect public markets (for instance, if a large private credit fund halted redemptions or a major real estate trust defaulted). The interconnectedness with traditional finance is also a concern – banks lend to these non-banks or sponsor their funds, so troubles can transmit. Regulators (like the Financial Stability Board) are increasingly focusing on non-bank risks, but policy tools are limited. Bottom line: the plumbing of the financial system outside the big banks could be a source of liquidity crisis. If credit market conditions worsen, keep an eye on things like bridge loan funds, leveraged loan prices, CLO (collateralized loan obligation) markets, and CDS on non-bank financial firms for early warning signs.

Photo by Sean Pollock on Unsplash Housing and Real Estate Markets: Real estate often plays a starring role in financial crises. Today’s housing picture is mixed. Residential real estate (housing) in the U.S. saw a cooldown in 2022–2023 as mortgage rates jumped above 7%, eroding affordability. Home sales volumes fell sharply, and home price growth cooled (even declined in some overheated markets) before stabilizing in late 2023. However, a 2008-style housing bust appears unlikely – lending standards were much stricter this cycle and most homeowners have fixed low-rate mortgages, insulating them (and banks) from rising rates. Mortgage default rates remain near record lows for now. The bigger worry is commercial real estate (CRE), especially offices. The pandemic-driven shift to remote/hybrid work has caused a collapse in demand for office space in many cities. Office property valuations are down 20–30% (more in some cases), which means many office buildings’ mortgages are underwater or close to it. As mentioned, default rates on office loans have spiked, and high-profile defaults (borrowers simply walking away from buildings) are making headlines. Banks – particularly regional banks – have large exposure to CRE loans, and although they’ve weathered it so far, a steady drip of losses could curtail banks’ lending capacity and erode confidence. Beyond offices, sectors like retail (shopping centers) were already under structural pressure from e-commerce and could face more stress if consumer spending pulls back. Household mortgages bear watching too in countries where variable-rate loans dominate (for instance, Canada, Australia, parts of Europe) – as rates reset higher, consumer defaults or spending cutbacks could rise, impacting those economies and possibly global financial institutions. In the U.S., the concern is more new buyers being locked out of the market (which hurts construction and related industries) since existing homeowners mostly enjoy low fixed rates. Nevertheless, housing is a traditional leading indicator – permits and starts in the U.S. fell in 2022/23, signaling weakness, though they showed signs of bottoming by early 2024. If the Fed’s rate hikes were to overshoot, a housing downturn could worsen. Real estate is also tied to consumer wealth and bank health, so continued troubles in CRE could yet catalyze a broader credit crunch. Importantly, real estate downturns play out slowly; the risk is a grinding drag on growth that suddenly reaches a tipping point if a major lender or fund fails. For example, a collapse of a heavily leveraged property developer (as seen in China’s Evergrande case) can have domino effects on contractors, suppliers, and banks. While the U.S. doesn’t have a comparable housing bubble now, commercial real estate is shaping up to be a slow-burning crisis that could accelerate under tighter financial conditions.

Other “Canaries”: A few additional indicators historically tied to downturns merit a mention. One is the money supply – an often overlooked statistic in modern policymaking. Unusually, U.S. M2 money supply contracted year-on-year in 2023 for the first time since the 1950s (The Rise and Fall of M2 | St. Louis Fed). Some economists (monetarists) argue that this monetary shrinkage portends deflationary pressure and a potential recession, given the lagged relationship between money growth and economic activity. While the Fed does not target M2, this unprecedented decline following an unprecedented surge has created uncertainty about how the economy will respond. Another indicator is the Leading Economic Index (LEI) from the Conference Board (mentioned earlier) – its long slide was one of the most reliable recession signals historically, and only very recently did its components diverge from a recessionary path (Conference Board gives up on U.S. recession call | Reuters). If the LEI resumes steady declines, it would indicate many forward-looking areas (new orders, permits, sentiment, jobless claims) are worsening in tandem. Surveys of loan officers (Fed’s SLOOS) we touched on show banks dramatically tightening credit standards, at levels seen in past recessions (Economic Effects of Tighter Lending by Banks - San Francisco Fed). Historically, every major tightening cycle in lending standards has been followed by an economic slowdown or recession (What We're Watching: What is the Fed's Senior Loan Officer Survey ...). Additionally, measures of financial market stress – like the St. Louis Fed’s FSI or the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index – have lately been benign, but can change quickly. One could also watch the U.S. dollar’s exchange rate: a rapidly strengthening dollar can stress emerging markets (who have dollar-denominated debts) and hurt U.S. exporters, whereas a rapidly weakening dollar could signal capital flight. Currently, the dollar is off its highs but remains strong compared to historical averages, and no currency crisis is evident. However, an example of a political risk: in fall 2024, one-year U.S. sovereign CDS spreads jumped to ~50 bps amid debt ceiling and election jitters (US sovereign credit default swaps rise on election, debt ceiling jitters), reflecting hedging against a U.S. technical default. Those fears subsided, but they will likely return when the debt ceiling deadline looms again (expected in 2025). Unmonitored trends could even include social factors – e.g., a sharp drop in consumer sentiment among certain income groups, or a rise in delinquency on credit cards and auto loans (which is happening, though from low levels). Each alone may not cause a collapse, but together they paint a picture of a late-cycle economy that is more fragile than surface metrics suggest.

4. Short-Term vs Long-Term Recession Risk Outlook

Short-Term (Next 6 Months) Outlook: In the immediate term, say through mid-2025, the U.S. economy faces a delicate crosswind of slowing momentum but still positive growth. The question is whether a “credit event” or cascade could occur that rapidly alters this trajectory. A credit event means a sudden default or liquidity crisis that triggers broader financial contagion – for instance, a major bank failure, a sovereign default abroad, or a meltdown at a large non-bank institution. We got a taste of this in March 2023 with the regional bank failures; that episode showed how quickly confidence can erode but also how swift policy response can contain panic. In the next 6 months, a plausible risk is a continuation of “rolling recessions” – specific sectors (housing, manufacturing, tech startups, commercial real estate) are in downturn, but not enough to pull the whole economy in. However, the cumulative effect of high interest rates is building. Many economists liken the current situation to a slow-burn where something eventually “breaks.” It could be a wave of corporate downgrades and defaults (as firms can no longer refinance cheaply) or perhaps a funding crunch for small banks (if depositors continue to chase higher yields elsewhere). The term “credit event cascade” implies one default leading to another – this is a concern particularly in leveraged sectors: for example, if a big private equity-owned company defaulted on its loans, that could hit the private credit funds, who might then restrict credit to other companies, causing more defaults. Are we approaching such a cascade? Thus far, credit stress has been contained – defaults have risen but mostly in smaller, isolated cases. The next 6 months will likely see increasing strain but not necessarily a breaking point. A key short-term indicator is liquidity: measures like interbank funding stress (LIBOR-OIS spreads) or corporate CP (commercial paper) rates. Currently, no acute liquidity crunch is visible. Also, household finances, while weakening, still have some cushion (the personal savings rate is low, ~3-4%, but not zero; excess savings still exist for middle/higher income groups). That suggests consumer default rates will climb only gradually near-term. In absence of an external shock, the more likely short-term path is a continued gradual cooling – slower job growth, possibly a slight rise in unemployment toward 4–4.5%, and inflation continuing to ease. This could resemble a mild mid-cycle slowdown rather than a sharp recession. Indeed, if one goes by the bond market’s expectations, the Fed is likely to start easing policy in the second half of 2025 (if not sooner) once they are confident inflation is durably lower. Such easing could extend the expansion. That said, the risk of a misstep or surprise is highest when the economy is flirting with stall-speed. One unforeseen shock – be it geopolitical (oil embargo, etc.), financial (a hedge fund blow-up), or policy (debt ceiling standoff) – could tip the balance. Short-term recession risk is therefore real but not a certainty. It’s worth noting that a number of large forecasters have repeatedly pushed out the recession start date as data surprises to the upside. By mid-2025, if those shocks haven’t materialized, we may simply see a slower economy, not necessarily a recession yet.

Longer-Term (2025–2026) Outlook: Looking further out into late 2025 and 2026, the probability of a recession or serious downturn may actually increase. This is because some factors that are not biting now will do so with a lag. For instance, a huge wall of corporate debt comes due in 2025–2026 (many companies issued bonds during 2020–21 that will mature) – they will need to refinance at much higher rates, which could severely squeeze their finances, possibly leading to a wave of restructurings or bankruptcies around 2025–26. Similarly, the commercial real estate “maturity wall” peaks around 2025–27, with nearly $1.2 trillion in CRE loans needing refinancing (Commercial Real Estate: When Maturity Means Default). If office valuations remain depressed, 2025–26 could see much bigger defaults and losses crystallize in that sector, potentially impacting banks and investors more broadly. Another longer-term concern is that by 2025, some of the post-pandemic tailwinds (like pent-up savings, strong job rebound) will have fully dissipated. Demographics, too, will reassert: labor force growth is slow, and productivity gains have been modest, suggesting trend growth in the U.S. might be only ~1.5–2%. This means the economy has less “speed limit” to work with and is more prone to slipping into recession with smaller shocks. Policy fatigue could also set in: fiscal policy was a big driver in 2020–21 but has turned into a drag as COVID programs ended. By 2025, with a new Congress and administration possibly, there may be either political gridlock or fiscal tightening (to address deficits) that removes stimulus from the economy. Indeed, if markets begin to balk at U.S. deficits (pushing Treasury yields higher), the government could be forced into austerity at an inopportune time. The Federal Reserve in the long run will also have to navigate when to cut rates – too early a cut could reignite inflation (a misstep the BIS warned against) (BIS Warns of High Debt Levels and Loan Defaults), but too late a cut could mean policy stays too tight for too long. The margin for error is thin. Fed officials have signaled they plan to hold rates “higher for longer” to avoid repeating the inflation flare-ups of the 1970s, but they also acknowledge they may need to ease if the economy clearly falters. We might see by 2025–26 a scenario where inflation is near target but the economy is losing steam – a classic end-of-tightening-cycle recession. On the other hand, if a recession doesn’t occur by 2025, we could face the risk of economic overheating again if policy is loosened and growth picks up, leading to another inflation surge – an alternate risk scenario. However, assuming the inflation fight is largely won by 2025, the bigger risk becomes insufficient demand. Historical precedent: the U.S. has never avoided a recession when the Fed hiked rates as much as it did in 2022–23 (~500 bps) – it sometimes takes 2–3 years for the full effect. So 2025–2026 might bear the brunt of the “long and variable lags.” Additionally, global factors in the longer term: China’s trajectory (could a sharp China slowdown in 2025 pull the world into recession?), Europe’s energy transition costs, and geopolitical realignments will shape the environment. If one had to anticipate a “collapse,” it often requires cumulative weaknesses to reach a critical mass – and those might indeed accumulate by 2025: high corporate leverage, diminished consumer savings, strained government finances, and some new shock could coincide. In the worst case, one could imagine a liquidity crisis emerging – for example, if in late 2025 multiple large companies default, banks pull back, and some part of the financial system freezes (maybe a major clearinghouse or money market issue), it could force emergency interventions reminiscent of 2008. This is not the base case, but longer horizons allow more time for bad combinations of events. Policymakers, however, would likely act forcefully at the first sign of such a cascade (as they did in 2020 and 2008). The presence of tools like the Fed’s standing repo facility, the bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) introduced in 2023, and ample bank capital means the system is more resilient than in the past to shocks – albeit new cracks can always emerge where least expected.

Policy Signals and Mitigation Plans: Both the Fed and the U.S. Treasury have indicated they will respond aggressively if systemic risks materialize. For example, the Treasury’s bank regulators and the Fed created backstop facilities during the March 2023 bank scare essentially overnight, extending liquidity against high-quality assets to banks (the BTFP allowed banks to borrow against bonds at par to avoid fire-sales) (Federal Reserve Board announces it will make available additional ...) (Federal Reserve Board announces it will make available additional ...). This shows a blueprint for handling a sudden liquidity crunch – likely, any sign of cascading defaults would see the Fed reopen or expand such programs to keep credit flowing. The Fed also has swap lines with other central banks to prevent dollar funding shortages globally. Meanwhile, the Treasury has worked on Treasury market stability (as noted, launching buybacks in 2024 to improve market functioning (Debt buyback program set to improve liquidity, says US Treasury ...)) to ensure that the government can always finance itself smoothly – crucial because a disorderly Treasury market can cripple the whole financial system. In the event of an extreme crisis, the U.S. government still has fiscal capacity to act (though high debt makes it contentious) – one could envision emergency stimulus or bailouts if needed, albeit those are politically harder now. Fed officials have subtly signaled they would sooner cut rates or pause quantitative tightening if financial stress escalates (“financial stability concerns” can trump inflation concerns in the short run). In fact, part of the reason the Fed has been cautious in 2023–24 is to avoid inadvertent stress – they slowed the pace of hikes and telegraphed moves to let markets adjust. They are also monitoring “unmonitored” sectors more closely (through the Financial Stability Council, etc.). So, on the policy front, there’s awareness and some preparedness to mitigate risks. However, the efficacy of policy may be limited if a shock is non-financial (e.g., a war or natural disaster) or if inflation is still uncomfortably high when a downturn hits (limiting the Fed’s willingness to ease). A potential blind spot is fiscal policy – a divided government might struggle to pass timely stimulus in 2025–26, especially if political brinkmanship (like debt ceiling standoffs) is in play. That could make any recession worse by lack of prompt support (unlike 2020 when trillions were deployed quickly). Thus, while short-term recession might be averted by nimble policy, the longer-term risk is that policy stimulus is late or insufficient when the economy eventually slips.

Historical Leading Indicators of Collapse: Looking back, major economic collapses (the 2008 financial crisis, the 2000 dot-com bust, etc.) often were preceded by a combination of asset bubbles bursting and credit crunches. In 2008, it was housing and subprime credit; in 2000, it was overvalued tech equities and corporate investment bust. For 2025–26, one could ask: what could be that trigger? The U.S. stock market, led by tech giants, has been quite elevated – if earnings disappoint or rates rise further, a significant stock market correction could erode wealth and confidence. Corporate debt is a likely trigger candidate: the “everything bubble” of 2010s led to very high corporate leverage (debt-to-GDP). A wave of corporate downgrades to junk status could force fire sales by investors who can only hold investment-grade debt, leading to a credit crunch. Additionally, an international trigger could be in play – perhaps a sovereign default in a major emerging market (some fear a potential crisis in countries like Turkey or heavily indebted nations if global rates remain high). Contagion from abroad can hit U.S. banks or markets (as in 1998’s Russia default and LTCM hedge fund collapse). One “unmonitored” trend could be the rapid rise of government debt service costs: by 2025, the U.S. will be spending a much larger share of its budget on interest, which could crowd out other spending or lead to sudden austerity if bond investors demand it. If investors lose confidence in U.S. fiscal sustainability (a low-probability but high-impact scenario), it could precipitate a currency crisis or bond selloff even for the U.S. – essentially forcing an ugly adjustment. Historically, this hasn’t happened to the U.S. in modern times, but smaller economies have suffered such fate. While the dollar’s reserve status provides insulation, it’s a risk not to be completely ignored given the trajectory of debt. Another often overlooked indicator is public sentiment and social stability – extreme economic stress can manifest in social unrest, which then further damages economic activity (for example, widespread strikes or protests as seen recently in some European countries over cost of living). In a severe downturn scenario for 2025, social strains could complicate recovery efforts.

In summary, short-term recession risk (next 6 months) is moderate – the economy is slowing but may skirt an official recession if nothing “breaks” abruptly. Longer-term recession risk (2025–2026) is more elevated as the delayed effects of tightening and various debt burdens come due, increasing the likelihood of a downturn or even a financial crunch. Policymakers are signaling awareness and willingness to intervene to prevent a collapse, yet some emerging trends (debt accumulation, geostrategic conflicts, climate shocks) are harder to manage and could emerge as the “surprise” triggers of the next crisis. Vigilance is warranted: just as the “credit boom” of the mid-2000s hid latent risks that exploded later, the current benign financial conditions (tight spreads, low volatility) could be hiding a build-up of stresses that only reveal themselves under pressure.

5. The Recession Watchguard Index and Risk Assessment

Drawing together these findings, I have created a “Recession Watchguard Index,” which tracks key risk factors and assigns probability estimates to potential triggers of economic instability. This index is a composite of various indicators and expert insights, translating them into an overall assessment of collapse risk. Below we can validate previous probability estimates and introduce new factors:

Credit Event Risk: Probability ~25% in the short term (next 6 months); ~35–40% in the 2025–26 horizon. This factor gauges the chance of a serious credit-induced crisis – e.g., a major default or liquidity seizure in financial markets. Based on the research, credit spreads are currently very tight (implying low immediate risk perception) (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab) (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab), but defaults are on the rise and cracks are forming (2024 saw a 14-year high in bankruptcies (Analyzing the Rise in Corporate Bankruptcies - LPL Financial)). We adjust this risk slightly downward in the near term since markets remain liquid and policymakers stand ready to backstop (as shown by the 2023 bank interventions). However, we adjust upward for the medium term: as high rates persist, the likelihood of a cascade of corporate or financial defaults grows. The BIS warning about “high debt levels and loan defaults” and vulnerabilities in commercial real estate and private credit reinforces an elevated risk in the coming years (BIS Warns of High Debt Levels and Loan Defaults). New contributing factors here include shadow banking stresses and the upcoming refinancing wall – these raise the medium-term probability that a credit event (or series of events) could trigger a recession or market crisis. While not our base case, there is roughly a one-in-three chance that credit stress could become the tipping point into an economic downturn by 2025.

Labor Market Deterioration: Probability ~30% (short term); ~50% (2025–26) of a significant labor market downturn. This measures the risk of the job market weakening substantially (unemployment spiking above, say, 5–6%). This research shows the labor market is still relatively strong but clearly cooling – unemployment up off lows, temp jobs down, and wage growth leveling (What happened to temps? Changes since the Great Recession : Monthly Labor Review: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute). In the short term, the probability of a sharp labor deterioration is moderate (perhaps ~30%) – firms are hoarding labor after past shortages and may be reluctant to cut staff quickly, which could delay a surge in joblessness. However, leading signs like the Sahm Rule trigger (unemployment up 0.5+ pts) have already occurred (The Sahm Rule Trigger: Is the United States in a Recession?), indicating a rising risk of broader job losses. For the long term, we increase this risk probability: if a recession hits in 2025, unemployment could easily jump into the 6–7% range. The watchguard index will monitor initial claims, job opening rates, and layoff announcements closely. New factors to include: the impact of automation and AI could start reducing certain job categories unexpectedly, and if consumer spending flags, businesses might finally cut payrolls more aggressively. So while the timing is uncertain, the chance of a notable labor market deterioration by 2025–26 is substantial (around 50/50). Remember, once layoffs start in earnest, they can feed a downward spiral in consumption – making this a critical component of collapse risk.

Policy Misstep Risk: Probability ~20% (short term); ~30% (medium term) of a major policy error exacerbating instability. This accounts for the risk that either monetary or fiscal policy actions (or inaction) worsen the situation. In the short run, the Fed appears quite vigilant and data-dependent – so an outright mistake like over-tightening or easing too soon is somewhat limited. The Fed has slowed its hikes and is watching financial conditions; the hurdle for a big policy error in the next 6 months is lower (hence ~20%). Still, miscommunication or delayed response could rattle markets (e.g., if inflation jumps and the Fed has to unexpectedly hike again, or conversely if a crisis erupts and the Fed hesitates due to inflation worries). Going into 2025, the policy misstep risk grows. A new administration or Congress might pursue populist economic measures (tax cuts or tariffs) that could be ill-timed. For example, if large tax cuts are enacted in an overheated economy, the Fed might slam the brakes harder; or if government shutdowns/debt ceiling standoffs occur during a fragile period, they could undermine confidence. The debt ceiling specifically is a policy-inflicted risk – a failure to raise it in time in 2025 could cause a technical default, something Treasury and the Fed cannot fully buffer against (we saw CDS spreads rise on this risk) (US sovereign credit default swaps rise on election, debt ceiling jitters). On the monetary side, the Fed might misjudge the neutral rate – cutting too late and causing an unnecessarily deep recession, or cutting too early and reigniting inflation (forcing another hiking cycle). The BIS has explicitly cautioned central banks not to “squander” the progress on inflation by easing prematurely (Central bank body BIS urges cenbanks not to squander interest rate ...), underscoring how policy navigations in 2025 will be tricky. We add to this category the risk of insufficient policy — e.g., central banks reaching the zero lower bound again without ample tools, or governments balking at stimulus due to debt fears (a form of policy error of omission). Given the many possible pitfalls, we edge this probability up. While outright policy blunders are not the norm, even smaller misjudgments at a delicate time can have outsized effects. The Watchguard Index will keep an eye on Fed meeting minutes, inflation trends, and political developments for early signs of policy going astray.

New Factor – Geopolitical/Energy Shock: Probability ~15% (short term); ~20% (medium term) of a severe external shock (war, energy spike) tipping the economy. This is newly added to our index considering the elevated global tensions and recent consumer/investor sensitivity to such issues. While it’s difficult to assign probabilities, we estimate perhaps a 15% chance in the next half-year of a shock disruptive enough to significantly alter the economic outlook (for example, a conflict that sends oil above $120, or a trade war that freezes major supply lines). Over a two-year horizon, that risk might rise to ~20% as these tensions simmer – the U.S. 2024 election aftermath, China-Taiwan relations, and other flashpoints will remain in focus. This factor is somewhat orthogonal to economic fundamentals – it could coincide with other risks (worsening a recession) or occur out of the blue. Monitoring indicators like commodity prices, defense spending, and diplomatic relations is key. The recent University of Michigan survey noting tariffs and inflation expectations shows how quickly geopolitics can feed into sentiment (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News) (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News). Thus, even absent a full shock, the threat of one can dampen investment (companies might delay capex due to uncertainty). Our index captures this as a risk that could accelerate a collapse scenario, even if it’s not the primary cause.

New Factor – Financial System Liquidity & Shadow Banking: Probability ~10% (short term); ~25% (medium term) of a liquidity freeze or shadow bank failure causing crisis. We add this recognizing that sometimes the spark comes from within the financial system in places people weren’t watching. Near-term, say 1 in 10 chance, because right now liquidity is decent and there are no obvious stress events brewing (funding markets are calm, VIX is low, etc.). But medium-term, this grows – as discussed, the longer high rates strain non-bank players, the more likely it is that a notable institution or market freezes up. For example, a large private credit fund could face a run; an alternative asset class (crypto, perhaps) might crash and have knock-on effects. We note that shadow banking issues have had global echoes already (China’s trust companies are in trouble, UK pension LDI issues, etc.), and the U.S. is not immune. The Watchguard Index will monitor things like the TED spread (interbank lending risk), money market fund flows, and any anomalies in short-term funding (commercial paper market, repo market rates). The Fed’s own Financial Stability Report has flagged life insurers and certain non-bank real estate investors as potentially exposed under stress (Central bank body BIS urges cenbanks not to squander interest rate ...). Because this is a harder-to-see risk, it warrants inclusion as a separate factor. It contributes to collapse probability insofar as it can turn a garden-variety recession into a sharper financial crisis if unchecked. As such, we assign a notable probability by 2025 that some unanticipated liquidity crunch emerges (perhaps 1 in 4 chance).

Considering all these factors, the overall probability assessment for economic instability, in the near term, has a chance of an outright recession in the next 6 months is perhaps around 35% (slightly above one in three, reflecting the many headwinds but also current resilience). The chance of a more severe “economic collapse” scenario (a 2008-style cascade of failures) in the near term is much lower – perhaps on the order of 10–15% – as it would likely require multiple triggers failing simultaneously. However, looking at a two-year horizon into 2025–2026, the cumulative probability of a recession becomes quite high (we’d put it above 60%, given historical patterns and the array of pressures). The probability of a severe financial crisis in that horizon, while still not the base case, also rises – perhaps 20–25% – especially if policy responses falter or new systemic risks emerge unseen.

To visualize the Recession Watchguard Index, we have:

Overall Recession Risk: ~35% near-term; ~65% within two years.

Overall “Collapse” (Systemic Crisis) Risk: ~10% near-term; ~20% within two years.

These aggregated metrics combine the sub-components discussed (credit, labor, policy, geopolitics, liquidity). We would adjust these probabilities dynamically as new data comes in – for example, if credit spreads suddenly spike or jobless claims jump, the near-term recession odds would ratchet higher.

Key Data Points and Insights Supporting the Update: The inversion of yield curves and rise of term premiums signal that bond markets remain anxious about the future (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters). Credit markets’ complacency (record-tight spreads) could be a calm before the storm, given rising bankruptcies (Analyzing the Rise in Corporate Bankruptcies - LPL Financial) and expected default increases. The labor market’s hidden softening (temp jobs falling, Sahm rule triggered) points to not being fooled by the low unemployment rate (What happened to temps? Changes since the Great Recession : Monthly Labor Review: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) (The Sahm Rule Trigger: Is the United States in a Recession?). Consumer sentiment is fragile and easily swayed by prices and policy news (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News). Manufacturing is in a global slump even as services hold up, a divergence that likely will resolve by services weakening (Flash PMI data shows US economic outperformance widening in December | S&P Global ). Expert forecasters like the Fed, IMF, and banks mostly see slow growth, not collapse, in the baseline – but even they concede many “red flags” are waving (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute) (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years). New risk factors like geopolitical tensions (tariffs, war risks) and shadow banking strains (private credit, CRE) are being increasingly cited in reports by institutions such as the World Bank and BIS (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years) (BIS Warns of High Debt Levels and Loan Defaults), validating our inclusion of them in the index.

Conclusion: This independent research broadly validates the concerns of a recession– many key indicators (yield curve, LEI, bank lending, temp jobs) indeed historically precede recessions and are flashing warning signs now. At the same time, certain markets (corporate bonds, equities) are not pricing in much risk, indicating a gap between financial conditions and economic undercurrents. Expert consensus leans towards a soft landing but with prominent voices urging caution and highlighting significant uncertainties ahead. By tracking a broad set of indicators (from yield spreads to credit defaults to global events), we improve our chances of spotting a turn in the economy or financial system early. As of now, the system is holding together – but pressures continue to mount. Prudence dictates preparing for a downturn even as we hope one can be avoided or at least softened.

Sources:

Brookings – Explainer on Yield Curve and Term Premium (The Hutchins Center Explains: The yield curve - what it is, and why it matters) (The Hutchins Center Explains: The yield curve - what it is, and why it matters)

Reuters – Term Premium Rebuilding and Yield Curve Movements (Jan 2025) (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters) (Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters)

Charles Schwab – 2025 Corporate Bond Outlook (Credit Spreads Tight) (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab) (2025 Corporate Bond Outlook | Charles Schwab)

S&P Global/Mises Institute – Temp Employment as Recession Indicator (What happened to temps? Changes since the Great Recession : Monthly Labor Review: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) (Recession Signal: Temp Jobs Are Falling Fast | Mises Institute)

Congressional Research Service – Sahm Rule Triggered by Rising Unemployment (Aug 2024) (The Sahm Rule Trigger: Is the United States in a Recession?)

U.S. BLS – Real Wages and Inflation (Feb 2024) (Real average hourly earnings increased 1.1 percent for year ending February 2024 : The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Univ. of Michigan Surveys – Consumer Sentiment Trends (Dec 2024 & Feb 2025) (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News) (Consumer sentiment drops as inflation worries escalate | University of Michigan News)

S&P Global PMI Report – Record Divergence: Services vs Manufacturing (Dec 2024) (Flash PMI data shows US economic outperformance widening in December | S&P Global ) (Flash PMI data shows US economic outperformance widening in December | S&P Global )

Benzinga/Bridgewater – High Corporate Profits Unsustainable, Slowdown Not Priced (2022) (Ray Dalio's Hedge Fund Sees More Pain For Wall Street - SPDR S&P 500 (ARCA:SPY) - Benzinga) (Ray Dalio's Hedge Fund Sees More Pain For Wall Street - SPDR S&P 500 (ARCA:SPY) - Benzinga)

Federal Reserve Speech – Barr on 2023 Banking Stress and Crisis Management (Speech by Vice Chair for Supervision Barr on financial stability - Federal Reserve Board)

Reuters – Conference Board Abandons Recession Call, LEI Trend (Feb 2024) (Conference Board gives up on U.S. recession call | Reuters) (Conference Board gives up on U.S. recession call | Reuters)

San Francisco Fed – Lending Standards Tightened to GFC Levels (May 2024) (Economic Effects of Tighter Lending by Banks - San Francisco Fed)

Reuters – JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs Recession Odds (Aug 2024) (J.P.Morgan raises odds of US recession by year end to 35% | Reuters) (J.P.Morgan raises odds of US recession by year end to 35% | Reuters); Goldman soft-landing odds (Mar 2024) (Recession Outlook: US Has 85% Chance of Soft-Landing, Goldman Sachs Says - Business Insider)

World Bank – Global Economic Prospects (Jan 2024), Weakest Growth in 30 Years, Recession Risk Receded but Hazards (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years) (Global Economy Set for Weakest Half-Decade Performance in 30 Years)

BIS via finews.com – Annual Report 2024, High Rates “Surprisingly Little” Crisis but Risks (loan defaults, CRE, private credit) (BIS Warns of High Debt Levels and Loan Defaults)

Reuters – US Corporate Bankruptcies at 14-year High (2024) (Analyzing the Rise in Corporate Bankruptcies - LPL Financial)

Fitch via S&P Global – CMBS Delinquency to Double by 2024 (Office-led) (US Commercial Real Estate Deterioration to Increase in 2024, Led ...)

Financial Times/Reuters – US Sovereign CDS spiked on debt ceiling fears (US sovereign credit default swaps rise on election, debt ceiling jitters)

(Morning Bid: Bonds flashing red, 'term premium' at 10y high | Reuters)